Pediatric critical care specialists at Johns Hopkins report that a test of their pilot program to reduce sedation and boost early mobility for children in an intensive care unit proves it is both safe and effective.

In a summary of the research, published online Oct. 12 in Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, investigators at the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center say their PICU Up! Early Rehabilitation and Progressive Mobility Program is intended to maintain or restore musculoskeletal strength and function. It includes activities such as sitting at the edge of the bed, standing, moving from bed to chair, walking and playing with toys.

The program demonstrated such success that other centers across the globe have contacted the research team for help implementing the program in their own institutions.

“We’ve long underestimated what children in pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) can safely do,” says Sapna Kudchadkar, M.D., assistant professor of anesthesiology and critical care medicine, director of the pediatric critical care clinical research program at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the study’s senior author.

“The prevailing belief is that children in the PICU should be heavily sedated to protect them from all of the stressors, such as the tubes, the strangers and the physical pain. But fluctuating between a state of awareness and sedation can cause delirium, physical weakness and post-traumatic stress disorder.”

In a bid to establish the safety and benefits of early mobility, and “shift the culture” away from heavy sedation, Kudchadkar and her team first developed a three-level activity plan depending on each child’s physical limitations. A working group of physicians, nurse practitioners, physical and occupational therapists, child life specialists, speech pathologists and others developed implementation guidelines and trained existing PICU staff members to use the program, which required no special equipment.

Then, from March through May 2015, they recruited 100 children ages 1 day through 17 years admitted to the Johns Hopkins PICU for at least three days. Previous research, Kudchadkar says, showed that adults who stay at least three days are at the highest risk for ICU-acquired muscle weakness and would therefore benefit most from early mobilization.

For a baseline comparison, the team first observed and recorded 465 mobilization activities in 100 patients; after implementation, they observed and recorded 769 mobilization activities. Overall, the proportion of children receiving at least one in-bed activity increased from 70 percent to 98 percent, and the proportion of children who walked by day three increased from 15 percent to 27 percent. The median number of mobilizations per patient by day three in the PICU doubled from three to six.

Of the 39 orally intubated children, none walked prior to PICU Up! implementation, compared to four out of 40 orally intubated children who did so afterward.

“The fact that even a few orally intubated children who were previously heavily sedated could be awake, alert and lucid enough to walk is likely to be an eye-opener for clinicians,” says Kudchadkar.

The team reported that the program also resulted in increased rates of physical and occupational therapy consultations, from 54 percent to 66 percent and 44 percent to 59 percent, respectively.

Kudchadkar also noted the impact of the program on PICU patients’ families, increasing opportunities for meaningful time together. “Even parents whose children passed away due to their critical illness during the study said that being able to communicate with their children and having them mentally present rather than sedated during those last moments was priceless,” she says.

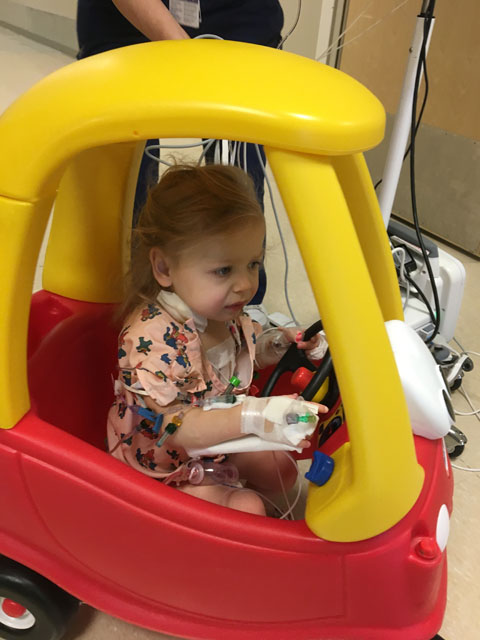

Matthew and Ashley Pearce, whose daughter Sydney was admitted to the Johns Hopkins PICU following open-heart surgery, recall how PICU Up! helped Sydney retain her sense of playfulness.

“We believe the program plays such an important role in recovery. We would never have thought that Sydney would be walking just 24 hours after surgery, and for as long as she did. Once she became more mobile, she was back to her old self, playing and dancing around,” say the Pearces.

Early mobilization, the family observed, seemed to reduce Sydney’s trauma. “The more Sydney was out of bed and the more she was able to move and play, the less she thought about where she was and what she had been through.

“When heading into something like a major surgery with a child, especially around 2 years old, a fear you have is what your child will be like when they come out of surgery. Will my daughter be the same fun-loving, happy, sweet girl, or will she become introverted and maybe stop talking all together? Knowing that there is a program there with the sole purpose of getting the kids back up and through recovery is so reassuring,” says the Pearce family.

Kudchadkar says her team’s finding demonstrate that “liberating” children in PICUs from heavy sedation as soon as possible and getting them moving earlier is possible and safe, but she acknowledges the challenge to conventional wisdom the new program poses.

“Mindset more than manpower has been the biggest barrier to implementing the program here and is likely to be the same elsewhere. Once clinicians see how effective the program is and how positively it affects patients and families, change will come,” says Kudchadkar.

Other authors on this study include Beth Wieczorek, Judith Ascenzi, Yun Kim, Hallie Lenker, Caroline Potter, Nehal J. Shata, Lauren Mitchell, Ivor Berkowitz, Frank Pidcock, Jeannine Hoch, Connie Malamed and Tamara Kravitz of The Johns Hopkins University, and Catherine Haut of the University of Maryland School of Nursing.

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (5KL2RR025006) and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Sommer Scholars Program.